NEY Michel - Twelve contemporary pamphlets and documents regarding his trial

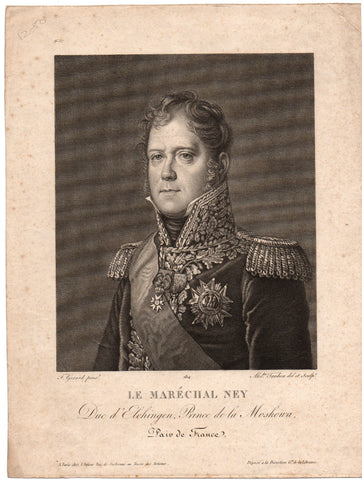

Michel NEY, Duc d’Elchingen and Prince de la Moskova (1769-1815)

Group of twelve off-prints, pamphlets and a news-sheet surrounding the trial of Marshal Ney as listed below:-

1. [Pierre-Nicolas] Berryer père. Plaidoyer . . . Prononcé en Séance publique, devant MM. Les Maréchaux de France, et les Lieutenans-Généraux des camps et armées du Roi, réunis en Conseil de guerre le 10 Novembre 1815 ; pour le Maréchal Ney, Prince de la Moscowa. Suivi du Jugement rendu par le Conseil. 38pp. 4to in French, n.p. [Paris], n.d. [10 November 1815].

A lengthy argument, setting out the reasons why Marshal Ney, as a Peer of the Realm, should be tried by the Peers of France rather than the military tribunal which had been convened. In the course of the argument, Ney’s lawyer, Berryer, sets out in a footnote that he (Berryer) had, since 1789, been an ardent Royalist, and was therefore undertaking Ney’s defence purely in the interests of justice, rather than from political inclination.

The last two pages consist of the Judgement of the Military tribunal, headed by Jourdan as its President and consisting of Massena, Augereau, Mortier and Lt.-Generals Cazan, Villatte and Caparède, declaring themselves incompetent to judge the case, and passing it to the Peers.

2. Michel Ney. Seconde Requete Présenté à la Chambre des Paires, le Jeudi 16 Novembre 1815, avant midi. 6pp 4to in French, n.p. [Paris], 16 November 1815.

Although the document is printed under Marshal Ney’s name, the tone indicates that it had very likely been drafted by his counsel. In it is set out what should be proper procedure for the trial, including a demand that any of the Peers who had publicly expressed an opinion against his innocence should disqualify themselves.

3. Dupin and [Pierre-Nicolas] Berryer père. Question Préjudicielle dans l’affaire de M. le Maréchal Ney. 14pp. 4to in French, Paris, 20 November 1815.

Opening with a quotation from article 4 of the Charter, stating that “no one may be pursued nor arrested except in cases foreseen by law, and in the form prescribed by it”, the document sets out in great detail the reasons why Marshal Ney should be acquitted, laying emphasis on legal precedent from the time of Henri IV.

4. [Anon.] Note Additionnelle. 2¼ pp. 4to in French, n.p. [Paris], n.d. [November 1815].

An argument refuting the Duke of Wellington’s reply to Ney’s wife, to the effect that the king of France had not signed the Convention of 3 July and was therefore not bound by the articles agreed therein.

A printed note at the end of the document remarks that copies of this had been sent to the Prince Regent and to the Prime Minister and their answer is awaited.

5. [Anon.] Pièces Relatives au Maréchal Ney. Extrait du journal anglais the public Ledezer [sic] and dayly Advertiser. 8pp. 4to in French, London, 22 November 1815.

A French translation of an article which appeared in a London paper. The first six pages consist of an argument strongly in favour of Marshal Ney’s case, appealing to article 12 of the Capitulation of Paris, signed by the Allies, which promised an amnesty to those who had previously been associated with Napoleon. When the point was made to the Duke of Wellington his reply was that although the Allies had signed the capitulation, Louis XVIII had not, and therefore could not be bound by it, and the Allies could not interfere in the affairs of France. The articule, though obviously written by an Englishman, entirely refutes and condemns this assertion.

The last two pages, unfortunately incomplete, are an excerpt from a despatch from Paris, in which further arguments are set forth for the dismissal of the case against Marshal Ney.

6. Dupin and [Pierre-Nicolas] Berryer père. Questions sur la manière d’opiner dans l’affaire de M. le Maréchal Ney. 13pp. 4to in French, Paris, 30 November 1815.

A document presented by Ney’s lawyers setting out very clearly the procedures the Peers should consider before commencing the trial. These include whether a simple majority of one vote is sufficient to condemn the accused (giving arguments from the ancient jurisprudence of France, British and American usage in law, the law of 29 September 1791 on the establishment of juries, and detailed arguments from the Revolution to the Consulate); whether Peers who are absent may vote by proxy; and whether the jury should vote viva voce or by secret ballot. The lawyers stress that the Peers’ decision on these matters will affect not only this trial, but also future trials.

An address on the verso of this pamphlet indicates that it was sent to the Comte de Beurnonville, one of the Peers who was to pass judgement on Marshal Ney. Although Beurnonville had fought for the Empire, he allied himself to the Bourbons at the time of the first abdication and remained loyal to them thereafter. He had been taken prisoner by the Austrians in 1793, but was one of the prisoners freed two years later in exchange for Marie Thérèse, last surviving child of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette, who was still incarcerated in France at the time.

7. Dupin and [Pierre-Nicolas] Berryer père. Effets de la Convention Militaire du 1 juillet 1815 et du Traité du 20 novembre 1815, relativement a l’accusation de M. le Maréchal Ney. 13pp 4to in French, Paris, 2 December 1815.

Part of the argument for the defence presented by Ney’s lawyers, Berryer père and Dupin.

The document presents convincing legal arguments in favour of the Marshal, citing legal precedent and, most importantly, arguing that the Convention, signed on 3 July 1815 by the Allies had stipulated that “all individuals in the capital [i.e., Paris] will continue to enjoy their rights and liberties without being troubled nor pursued for anything relating to the functions they fulfil or had fulfilled, their conduct of their political opinions”, effectively an amnesty for all who had served Napoleon.

8. M[aitre] Berryer. Exposé Justificatif pour le Maréchal Ney. 20pp. 4to in French, n.p. [Paris], n.d. [November/December 1815.

This constitutes the major argument for the defence, giving, in great detail, the chronology of events from Marshal Ney’s recall to service once Napoleon had arrived in France, false information received, his encounter with Napoleon, and the aftermath, ending with a vigorous defence of Ney’s honourable character.

9. T***. Réflexions sur Les Mémoires Justificatifs pour le Maréchal Ney. 11pp 4to in French, Paris, 1815.

The only pamphlet in the present collection which is fiercely pro-Royalist and condemns Marshal Ney without pity. The author writes of the marshal appreciating the ten months he had lived under the reign of Louis XVIII, when “peace, agriculture and commerce flourished in France, joy reborn, all wounds almost healed . . .”

10. Niles’ Weekly Register. 14pp. large 8vo, Baltimore [Maryland], 3 February 1816.

An American newssheet, combining local information (complaints about slow and irregular mail service), national news (reports from the U.S. Treasury) and a three-column article on the execution of Marshal Ney. The report speaks admiringly of the Marshal’s calm and dignified conduct during his last hours and at the moment of execution. A final paragraph makes the Weekly Register’s point of view abundantly, and bluntly, clear: “There seems a determination in the allies, through the deputy king, to kill every man whose genius may disturb the “repose” of despotism. The battle of Waterloo (won by gold as history shall tell posterity) is yet to be consummated in the destruction of the heroes of France . . .”

11. [Anon.] An Authentic Account of the Trial of Marshal Ney … preceded by a Memoir of his Life. 72pp. Glasgow, 1834.

A work translated from the French, and the Translator’s Preface makes the English (or more likely Scottish) translator’s sympathies quite clear: “. . . there was something vindictive in his punishment; and we could have wished that the future historian of our own great Captain [i.e., Wellington] might have had it to tell, that he raised his voice on the side of clemency . . .” In a final note with which many translators will sympathise, he adds that “those who are best acquainted with the heroic style of modern French writers, will best appreciate the difficulty which an English translator experiences in taming it down to the narrative style of English history.”

There follows a Memoir of Marshal Ney, half devoted to his military career, and the balance of his actions following Napoleon’s return from Elba. The second half of the pamphlet is devoted to an account of his trial. Although taken from a French source, there is a translator’s footnote in the section devoted to the trial: “We cannot help expressing our disgust at the manifest injustice of this decision of the Chamber, and the sophistry of the grounds of it; viz. that the king was no party to the Convention of the 3rd July, which is false in point of fact . . .” and speculating that had another battle taken place [after Waterloo] it would have been impossible to “predict what might have been the result, or whether . . . the obnoxious family of Bourbon would ever have sat upon the throne of France.”

12. Causes Célèbres de Tous les Peuples . . . Le Maréchal Ney (1815). 32pp. 4to in French, in wrappers, n.p. [Paris], n.d. [after 1853].

A lengthy, detailed account of events from the return of Napoleon up to the execution of Marshal Ney, including a partial transcript of the trial itself. The account ends with a final note of the erection of the statue to Marshal Ney in the Luxembourg Gardens in 1853 during the reign of Napoleon III. The pamphlet includes a number of illustrations of events in the Marshal’s life.

The trial and execution of Marshal Ney is without doubt one of the great miscarriages of justice in the annals of French history. Indeed, in one of the documents here, it is compared to the trial and execution of Louis XVI and of the duc d’Enghien. Like the duc d’Enghien, Marshal Ney emerges from this sad episode with far more honour and credit than his persecutors.

Ney’s wife had taken the unusual, but very clever, step of calling upon a convinced Royalist to defend her husband. Pierre-Nicolas Berryer, a respected and highly capable lawyer, declares himself in one of the documents here as a royalist from 1789, insisting that at no time had he espoused the principles of the Revolution, Directoire, Consulat or Empire. He called in Dupin, an accomplished orator, to assist him.

However, she turned away the offer of help from Maitre Bellard, who had been a friend of Ney. Bellard was later appointed prosecutor, and his anger at having been refused made him especially ardent in his attack.

Ney was to have been tried by a jury of Marshals and generals. But when Ney announced that he would find it unsuitable to be tried by any but his peers – and he was still a Peer of France – the initial jury, presided over by Jourdan and including figures such as Massena, Augereau and Mortier, declared itself incompetent to preside. They came to this conclusion with some relief; Massena in particular had pleaded that his disagreements with Ney during the Peninsular War were so well known that he could not be considered an impartial judge.

The second jury, made up of several hundred Peers of France (many of them, of course, declared Royalists) would prove far harsher, and one can only wonder as to why Ney chose not to accept the trial by his former comrades in arms, who could have been relied on to deliver a less disastrous verdict.

Louis XVIII himself certainly saw the danger of executing a popular, heroic Marshal of France, and probably colluded in creating an opportunity for Ney to escape before his trial. But Ney was too honest to think that the world would not treat him with the same honesty, and preferred to remain to clear his name.

The argument about article 12 of the Capitulation returns in most of the documents included here. Article 12 guaranteed a general amnesty to all those who had worked or fought under the previous regime, allowing the country to heal its wounds. Under those terms, Marshal Ney should never have been tried. But Louis XVIII had not signed this, only the Allies – Russia, Britain, Prussia and Austria – and those Allies insisted that they could not interfere. This was Wellington’s response to Ney’s wife when she pleaded with him – despite the fact that Louis would never have returned to his throne had it not been for the Allies’ consent.

And so Marshal Ney was condemned to death, with 161 members voting for the death penalty, 17 for banishment, 11 for exile among his relations and 5 asking for clemency. His fiercest enemy, the Comte d’Artois, succeeded to the throne as Charles X, perhaps the most unpopular king in French history, and was deposed in 1830. In 1848, the government voted that a statue be erected, at the place of his execution, to Ney, the ‘bravest of the brave’.

Delivery

Autographs can be delivered worldwide. Delivery costs are calculated at the time of order and items will be sent by the most appropriate means, depending on your location and the value of the item. This will usually be by Royal Mail Special Delivery within the UK and Royal Mail Tracked outside the UK.

The current delivery charges are:

-

UK:

Royal Mail Special Delivery £9.00

-

Europe:

Europe Royal Mail Tracked £15.00

EU customers should note that, following brexit, local VAT and customs duties may apply to their purchases.USA:

-

Tracked £25

Rest of the World:

-

Rest of the World Tracked £20.00

Export Licensing

Customers should be aware that all letters and documents over 50 years old require an export licence, which may delay delivery by anything from one to three weeks. Signed photographs are not subject to export licence regulations, and can be sent immediately.

There is no charge for the export licence and I will take care of the application, the only inconvenience to you will be the delay.

Authenticity

The authenticity of the letters and documents offered is guaranteed.

Payment

Online sales orders

Payments made via the website are processed by Shopify Inc and can be made using Visa, Mastercard or American Express.

Telephone sales orders

Items may be purchased by phone. Please contact me using the website Contact Form and I will call you within 48 hours to discuss your requirements. Payment for purchases ordered by phone can be paid upon receipt of the invoice and must be paid within 7 days. Phone orders can be paid by cheque (in pounds sterling only) or bank transfer.

Items will be reserved for one week following the order confirmation and will be dispatched either within 7 days after full payment has been received, or after any required export licenses have been granted.

Returns Policy

Should you be in any way dissatisfied with your purchase, items may be returned within six weeks of delivery and a full refund will be made upon receipt of the returned item. The item must be received by Richmond Autographs in the same condition as when dispatched. For full details, please read our Terms and Conditions.